- info@ficci.org.bd

- |

- +880248814801, +880248814802

- Contact Us

- |

- Become a Member

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Bangladesh stands at a critical juncture in its energy journey. With rising demand, a reliance on expensive fossil fuel imports, and global climate commitments, the transition to renewable energy has become imperative. The country has set an ambitious target of generating 40% of its electricity from clean sources by 2041. However, with renewables accounting for less than 3% of installed capacity today, significant structural and financial reforms are needed to achieve this goal.

The shift to renewables is not just about sustainability; it is an economic necessity. Bangladesh's dependence on imported fuel places significant pressure on foreign exchange reserves, exposing the economy to volatile global markets. Solar and wind energy, on the other hand, offer a long-term solution-one that enhances energy security, reduces costs, and attracts international investment. But unlocking this potential requires urgent action on policy, finance, and infrastructure.

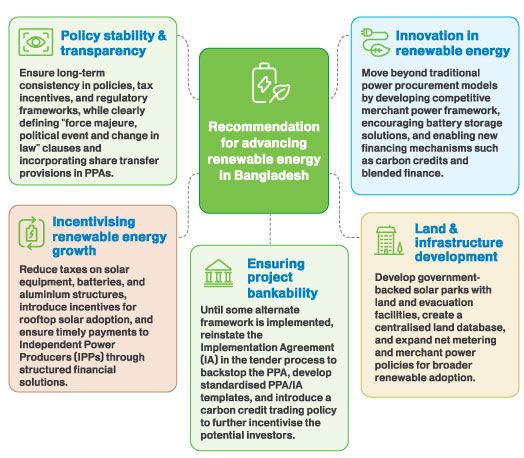

Policy as a Catalyst

For investors and developers, stability is key. Bangladesh has made strides in expanding renewable energy, but uncertainty regarding policy continuity and unforeseen changes in regulation remain challenges for scalability. The cancellation of Letters of Intent (LOIs) for solar projects awarded by the previous administration and uneven taxation policies for imports by Independent Power Producers (IPP) compared to Net Metering (NEM) system operators have sent mixed signals to investors.

To shore up confidence, the government must provide a stable, transparent, and consistent regulatory framework that encourages long-term investment.

The introduction of the Merchant Power Policy, which allows producers to sell electricity directly to consumers, is a positive step toward reducing dependence on government procurement. Similarly, the expansion of net metering policies to single-phase and small-load (with sanctioned load of less than 7 kW) - customers will make rooftop solar more viable. However, further clarity is needed on implementation and pricing mechanisms to ensure bankability.

Since land procurement and development is the main component of project cost in a highly populated country like Bangladesh, developing solar parks with evacuation facilities in unutilised government land owned by SOES, economic zones, khas lands, tea plantations and similar areas can be explored. This can significantly reduce project risks, ultimately accelerating large-scale deployment.

At the same time, Bangladesh must embrace emerging giga-green technologies such as advanced energy storage, grid-scale batteries, and green hydrogen. The European Union's commitment to adding 27 GW of wind power and 24 GW of solar annually by 2030 highlights the scale of transformation required. Bangladesh can take notes from these efforts to integrate the latest technological advancements into its energy transition strategy.

The Financing Puzzle

One of the biggest hurdles to scaling renewables in Bangladesh is access to affordable financing. It is estimated that the emerging markets, including Bangladesh, need $3.5 to $4 billion annually in transition finance to reach net-zero by 2050, with a major portion required for renewable energy projects. Private investment must be at the forefront of this transition, but for that to happen, projects must be bankable.

Under the present framework, where BPDB is the sole off-taker, standardised Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) and Implementation Agreements (IAs) are essential for attracting investment, especially from foreign lenders. The removal of sovereign payment guarantees has made financing more difficult, and alternative risk mitigation mechanisms-such as blended finance and partial credit guarantees-must be explored. In the medium to long term, development of the ecosystem for sale through bilateral PPAs with large-scale corporates and implementing a merchant power framework for trading power through renewable energy exchanges, should be explored to reduce dependence on government intervention and create bankability based on commercial merit of the project and creditworthiness of the developers and sponsors.

Additionally, tax structure on critical renewable energy components, such as solar panels, inverters, and batteries, must be re-evaluated, in order to make the final pricing competitive. High import duties on batteries-essential for energy storage solutions-hinder the scalability of renewable projects. Given that advanced battery solutions (including recycling of old batteries) will be critical in balancing energy supply and demand, particularly in a grid increasingly powered by renewables, Bangladesh must follow global best practices in incentivising battery adoption.

Globally, blended finance has emerged as a successful model for financing sustainable infrastructure, particularly in emerging markets. Partnerships between governments, development finance institutions, export credit agencies, and commercial banks have unlocked billions in funding for renewable energy projects. Bangladesh must proactively engage in such financing structures to scale up its clean energy ambitions.

The carbon credit market also presents an untapped opportunity. By leveraging its renewable energy potential, Bangladesh can generate carbon credits that can be sold to global buyers, creating an additional revenue stream for renewable energy projects. This will enable a reduction of overall tariffs and dovetail with the strategy of mass roll-out of micro-scale NEM based photovoltaic solar systems by creating a large pool of carbon credits aggregating the carbon emission reduction by all the operators.

A Collaborative Path Forward

Achieving Bangladesh's clean energy ambitions requires a coordinated effort between policymakers, financial institutions, and the private sector. The transition is not just about adding renewable capacity; it is about modernising the entire energy ecosystem-investing in grid infrastructure, adopting digital solutions, and creating an open market for power generation and distribution.

While progress is being made, much more is needed. Bangladesh must prioritise long-term policy stability, mobilise private, institutional and multilateral capital, mobilise climate adaptation funds and embrace cutting-edge green technologies to accelerate its transition. The window for action is narrowing, and the decisions made today will define Bangladesh's energy landscape for decades to come.